HPIC Analysis of Phosphite Treated Turfgrass

HPIC Analysis of Phosphite Treated Turfgrass – John Dempsey BSc (Hons)

Introduction

Potassium phosphite is regularly applied to amenity turfgrasses as part of routine maintenance programs. Phosphite (PO33-) is derived from the alkali metal salts of phosphorous acid - H3PO3, which when in contact with water forms phosphonic acid (Guest and Grant, 1991; Rickard, 2000). The pH of this acid needs to be modified prior to use to prevent phytotoxicity (Ouimette and Coffey, 1988) and this is most commonly done with the addition of potassium hydroxide (KOH), forming potassium dihydrogen phosphite (KH2PO3) or dipotassium hydrogen phosphite (K2HPO3). These compounds are the active substances in numerous phosphite products which have been used in commercial horticulture and turfgrass management since the 1980’s (Landschoot and Cook, 2005). Initially phosphite was used to control Oomycete pathogens –Pythium spp. (Cook et al., 2006; Schroetter et al., 2006). It was later found that combined with Mancozeb, a dithiocarbamate fungicide (Beard and Oshikazu, 1997) phosphite could improve significantly turf quality and also control Summer Decline of bentgrass (Cook et al., 2006). At present phosphite products are extensively marketed and used in amenity turfgrass management as both fungicides and biostimulants and while research into the efficacy of phosphite in these areas has been carried out (Sanders, 1983; Vincelli and Dixon, 2005; Horvath et al., 2006; Cook et al., 2009), there is none specifically into phosphites assimilation and translocation in turfgrass.

This research was carried out to determine the assimilation rate, translocation and accumulation of phosphite in a commonly used cool-season turfgrass – Agrostis stolonifera. Turfgrass tissues, treated with a foliar application of potassium phosphite were subject to High Performance Ion Chromatography (HPIC) analysis to determine PO33- and PO43- (phosphate) amounts in leaf, root and crowns. It was determined that phosphite is rapidly absorbed through the leaf tissues and readily translocated through the plants vascular system, there were no significant increases in the PO43- levels in planta indicating that PO33- is not readily metabolised to usable forms of P.

Methodology

Treatments

Agrostis stolonifera, established in PVC growth vessels, filled with USGA specification rootzone sand, were subject to foliar applications of potassium phosphite (KH2PO3). The applications replicated standard turfgrass management rates of 0.35 g/m-2 of H3PO3. Harvesting of the leaf and root tissues was carried out at pre-determined time periods: 1, 6, 12, 24, 48 hours and 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 weeks post application (p.a), crowns were harvested at 4 and 6 weeks p.a., un-treated control plants provided a standard comparison. Leaf tissues were collected using a scissors, at the set time periods, washed and rinsed in distilled water, dried with tissue and then dried at 600C for 48 hours. Roots were collected by placing the rootzone into a sieve and shaking to remove the soil. The roots were then washed and dried as above. Crowns were harvested by firstly removing the leaf tissues and then slicing the crowns away from the roots using a knife; they were then washed and dried as above.

The dried tissues were finely ground and 0.5g were extracted into 10ml of water overnight, passed through a 0.47 micron filter and injected into the sample loop of a Dionex HPIC system using a 9mM sodium carbonate eluent. Results are reported as parts per million (ppm) of dry tissue weight.

Results

PO33- accumulation

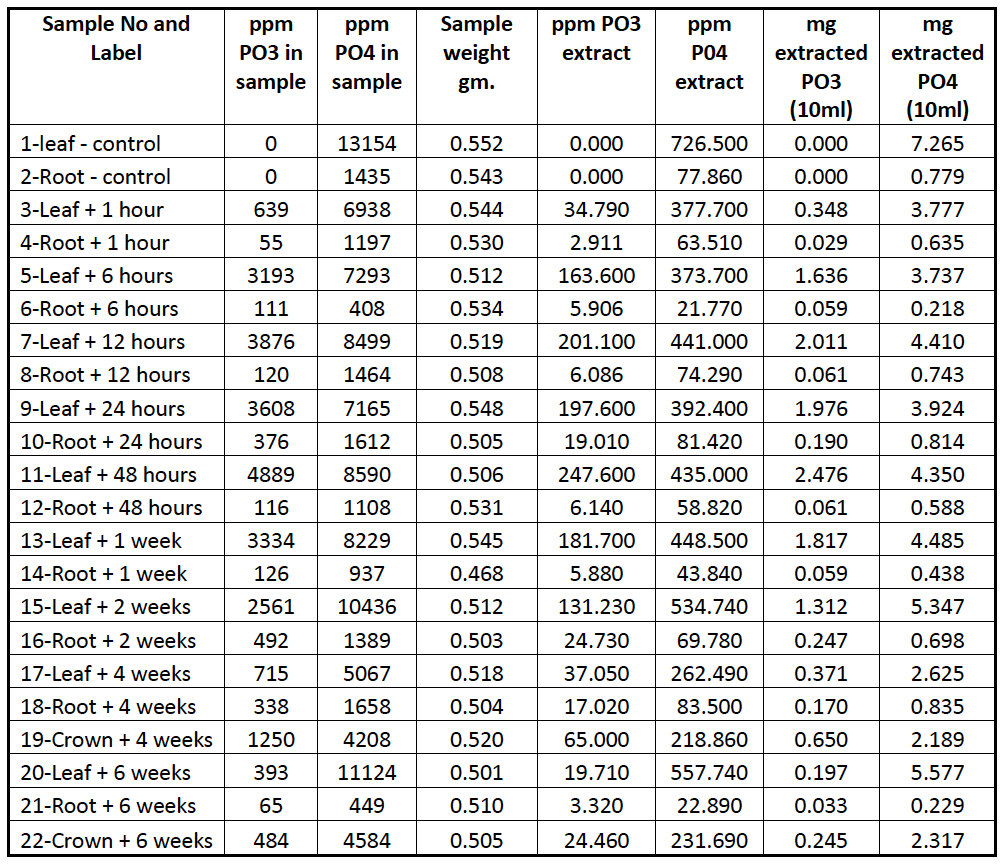

Table 1 shows the data from the HPIC analysis and from these data figures 1, 2 and 3 were configured. The data show that the highest rate of PO33- accumulations in the leaf tissues were 48 h p.a. with a figure of 4889ppm, accumulations of 639ppm (13% of maximum accumulation) 1 h p.a. and 3193ppm (65%) 6 h p.a were also determined. Two weeks p.a accumulations in the leaf were at 2561 ppm, approximately 50% of the maximum and gradually declined to 393 ppm at 6 weeks p.a.

Table 1 Data from HPIC analysis –sample weight, mg extracted and ppm for each sample.

In the roots, accumulations were less than in the leaf tissues, with the highest rate of 492 ppm, achieved 2 weeks p.a, and accumulations of 55ppm (11%) 1 h p.a. and 111ppm (23%) 6 h p.a.

Analysis of the crowns from 4 and six weeks p.a showed levels of 1250 and 484 ppm respectively.

Figure 1

PO33- accumulations in leaf and root tissues of A. stolonifera

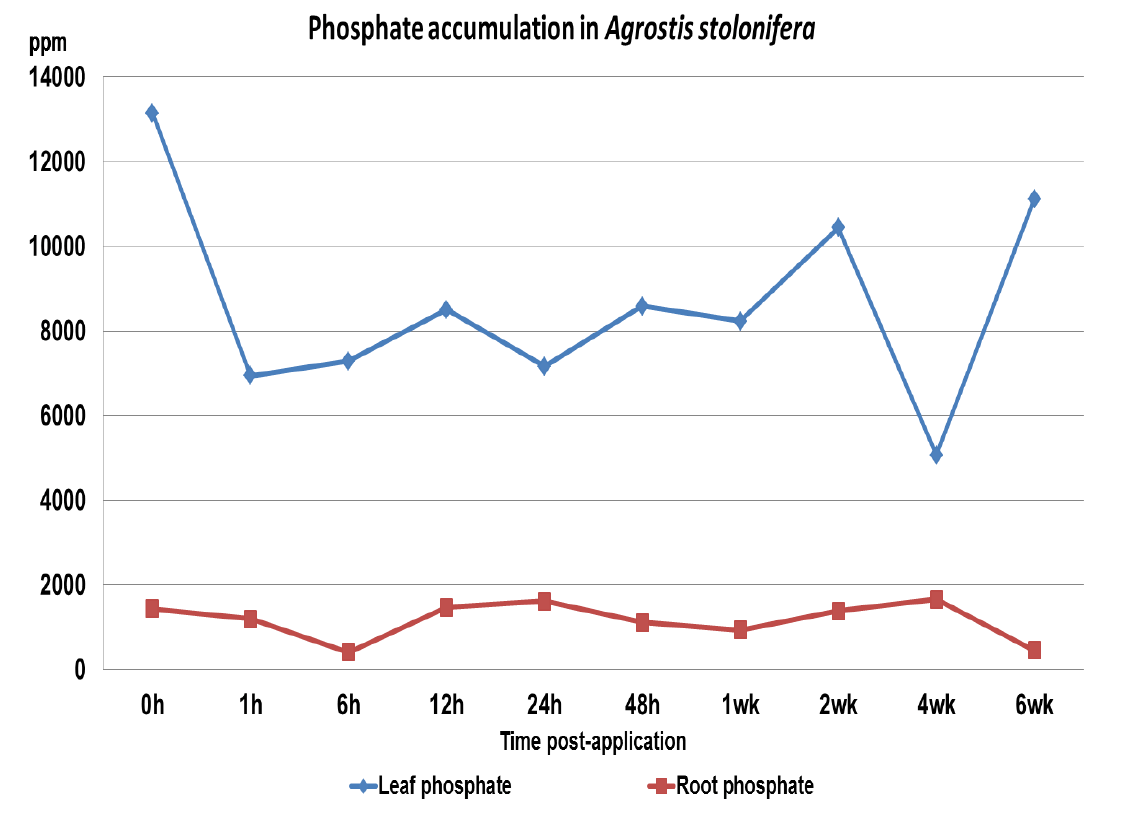

PO43- accumulation

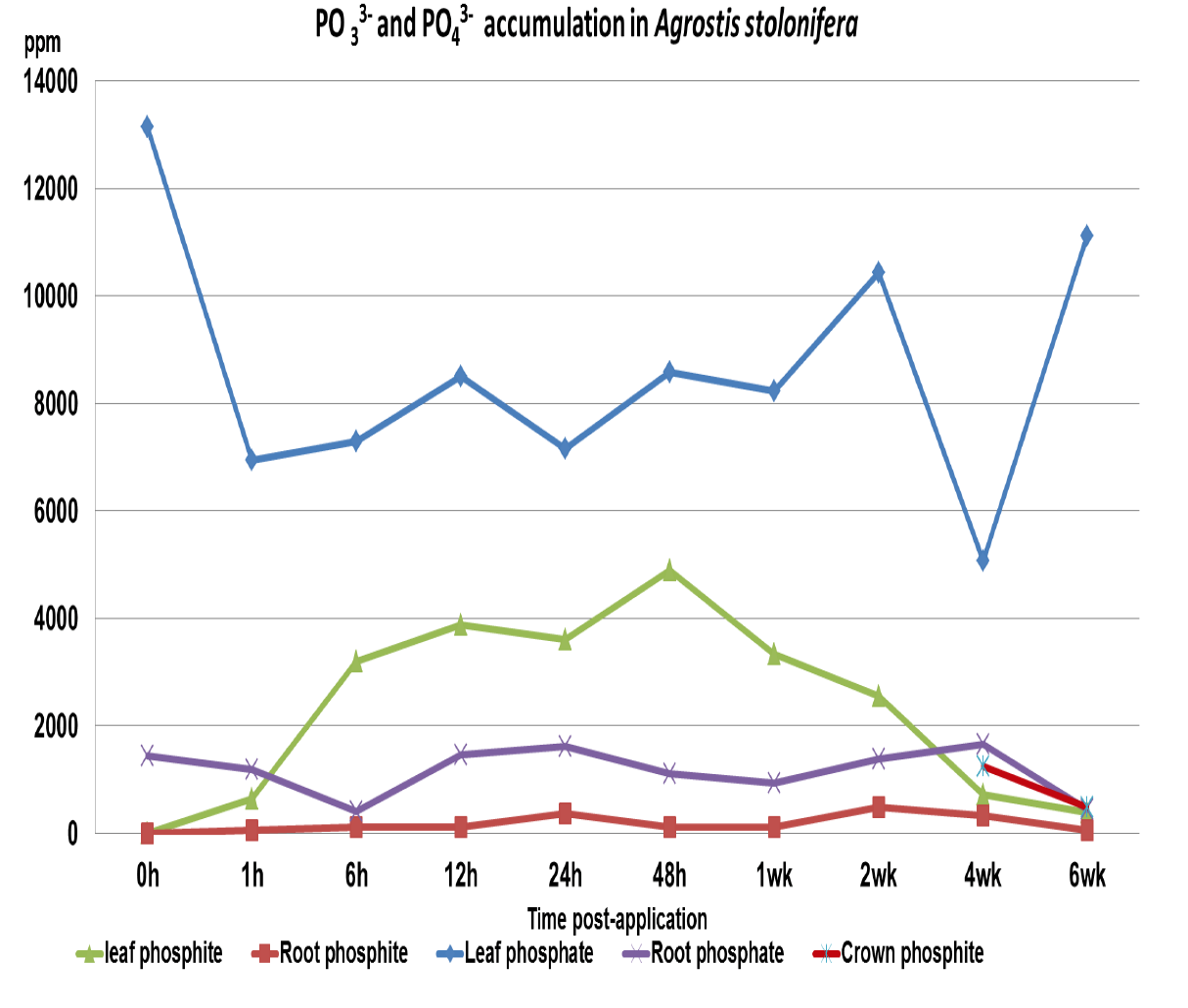

PO43- levels had a mean value of 8092 ppm for leaf and 1136 ppm roots, which are within the standard recommended levels for A. stolonifera. During the six week period of these analyses the PO43- levels did not vary significantly from the mean value, indicating no in planta conversion of PO33- to PO43-, figure 3 shows the combined PO33- and PO43- accumulations over the six week period.

Figure 2 PO43- accumulations in leaf and root tissues of A. stolonifera.

Figure 3 PO33- and PO43- accumulations in A. stolonifera over six weeks post application.

Conclusions and further reseach

The significant points from these analyses are, firstly- phosphite is rapidly assimilated into the leaf tissue of turfgrass and is translocated both in the xylem and phloem demonstrating symplastic ambimobility within the tissues. The second point of interest is that there was no significant increase in the PO43- levels, indicative that there is no rapid conversion of phosphite to phosphate within the plant. Even though the treatment and analyses were carried out during February, a period of low growth and metabolism, assimilation into the leaf tissues was rapid, achieving 65% of the maximum amount within 6 hours of application –a significant point for turfgrass managers; it could be assumed that assimilation could be more rapid during higher growth conditions. The level of phosphite within the leaf began to reduce after 48 hours and at 2 weeks p.a. had dropped to 50% of the maximum accumulation, as most management programs apply phosphite on a 2 to 3 week cycle this would indicate that levels would remain within the range of between 2500 to 5000 ppm throughout the term of the program.

Further research is required in this area, the above study was carried out on greenhouse samples with four replications for each analysis, which may have allowed some anomalies in the data, and field studies have now begun using a 1,200 m2 turf nursery, which will allow for a wide range of sample collection, increasing the validity of the data. These field studies will gather data to hopefully answer a number of unresolved issues-

Data relating to the in planta fate of PO33- for example, over a longer application period, six months to a year, does continuous treatment with phosphite lead to a cumulative increase in the tissue levels and where in the plant does phosphite accumulate – within the cells or extracellular spaces, is there a build up over time in meristematic areas, is there any in planta metabolisation to other forms of P over a longer period than the six weeks of first analyses.

References

Beard, J. and Oshikazu, T. (1997). Colour Atlas of Turfgrass Diseases. . New Jersey, Wiley and Sons.

Cook, J., Landschoot, P. J. and Schlossberg, M. J. (2006). "Phosphonate products for disease control and putting green quality." Golf Course Management: 93-96.

Cook, P. J., Landschoot, P. J. and Schlossberg, M. J. (2009). "Inhibition of Pythium spp. and Suppression of Pythium Blight of Turfgrasses with Phosphonate Fungicides." Plant Disease 93(8): 809-814.

Guest, D. and Grant, B. (1991). "The Complex Action of Phosphonates as Antifungal Agents." Biological Reviews 66(2): 159-187.

Horvath, B. J., Mccall, D. S., Ervin, E. H. and Zhang, X. (2006). "Physiological Effects of Phosphite Formulations on Turfgrass Challenged with Pythium and Heat Stress. Year II.".

Landschoot, P. J. and Cook, J. (2005). "Sorting out the phosphonate products." Golf Course Management: 73-77.

Ouimette, D. G. and Coffey, M. D. (1988). "Quantitatave analysis of organic phosphonates, Phosphonate, and other Inorganic Anions in Plants and Soil by Using High-Performance Ion Chromatography." Phytopathology 78(9): 1150-1155.

Rickard, D. A. (2000). "Review of phosphorus acid and its salts as fertilizer materials." Journal of Plant Nutrition 23(2): 161 - 180.

Sanders, P. L. (1983). "Control of Pythium spp. and Pythium Blight of Turfgrass with Fosetyl Aluminum." Plant Disease 67(12): 1382-1383.

Schroetter, S., Angeles-Wedler, D., Kreuzig, R. and Schnug, E. (2006). "Effects of phosphite on phosphorus supply in corn (Zea mays)." Landbauforschung Volkenrode 56: 87-99.

Vincelli, P. and Dixon, E. (2005). "Performance of selected phosphite fungicides on greens." Golf Course Management.